‘Taking care of a child with HIV is a heavy burden’

Ending the neglect of kids with HIV in West Africa

In the shade of a large mango tree, at the Albert Royer National Children's Hospital in Dakar, young children play under the watchful eyes of mothers and grandmothers who wait patiently, seated on a bench. In this quiet oasis of care in the middle of the bustling Senegalese capital, children living with HIV are treated with an abundance of affection - and discretion.

‘It's a secret disease,’ says a grandmother with a radiant smile, who came with her 9-year-old grandson whose two parents died of AIDS. ‘Taking care of a child with HIV is a heavy burden. A secret to keep.’

‘In Senegal, people with HIV are subject to harsh discrimination. Mothers are hiding. They don't want to be seen entering this pavilion. They are afraid to go to the pharmacy. They refuse to be followed up in their neighbourhood. As a result, many children living with the disease are not being detected. ’

Such stigma has deadly consequences. Children living with HIV are already neglected and in West Africa, this neglect is even deeper. In Africa, only 54% of children living with HIV receive antiretroviral treatment, as opposed to 74% of adults. In Central and West Africa that figure drops to 35% of children. Without treatment, half of these children die before reaching the age of two. Worldwide, a child dies of HIV every 5 minutes.

These difficulties are well known to the women of ABOYA, a local NGO located in the busy neighbourhood of Guédiawaye, a few kilometres away.

‘Women with HIV in Senegal are victims of physical and verbal violence and are subject to stigma that prevents them from accessing care,’ explains its director, who wants to stay anonymous.

ABOYA helps women living with HIV to navigate daily life. Its members asked to speak anonymously when they met a DNDi delegation in their office – a large apartment with many visitors and kids, in a location that they prefer to keep secret.

‘Most women living with HIV are afraid to share their status because they fear being excluded from their homes, being rejected by their husbands. Even at the hospital level, we have many problems with some midwives who refuse to take care of them and are even afraid to touch them.’

Members of ABOYA play a crucial role in supporting mothers and their children at every step. They provide medication when women cannot get it themselves. They take them to hospital if needed. They also provide assistance to women to help them prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV by taking antiretroviral medicine during pregnancy. They also ensure that infants born with HIV have access to treatment and are followed up by healthcare professionals.

The organization also engages in income-generating activities, such as producing bleach for hospitals in the capital. ‘This is necessary because HIV makes you poor. Women who have lost their husbands, or have been rejected, or abandoned find themselves without income,’ explains the woman in charge.

Bleach produced by women of ABOYA and sold to hospitals in Dakar

Bleach produced by women of ABOYA and sold to hospitals in Dakar

Bleach produced by women of ABOYA and sold to hospitals in Dakar

Bleach produced by women of ABOYA and sold to hospitals in Dakar

Pediatrician Dr Ndièye Fatou Diallo, at Albert Royer Hospital, testifies that these daily tragedies and difficulties can take a heavy toll on the morale of her small, dedicated team of doctors, nurses, and counsellors.

‘Some days, it is so hard. When we go home, we can't eat. We just can't. Fortunately, we have a great team here!’

Dr Fatou Diallo surrounded by the paediatricians, nurses, and counsellors of the paediatric HIV team.

Dr Fatou Diallo surrounded by the paediatricians, nurses, and counsellors of the paediatric HIV team.

Albert Royer began treating children with HIV in 2000. The team manages the children's medical follow-up - including monitoring their viral load - and provides psychosocial support to families.

‘The situation has improved over the past 20 years, but we still have many challenges to face, such as screening siblings and improving care,’ says Dr Fatou Diallo.

Even when antiretroviral treatments are available and free, access remains a problem, particularly in more rural areas, emphasizes ABOYA’s director.

‘The situation in the villages is extremely difficult. Some mothers live in the mountains, others on islands, where the distance between home and the healthcare centres complicates follow-up assessments, management of opportunistic infections, and of course procuring medication.’

These access issues and the harsh stigma surrounding the disease in Senegal only compound the problem of neglect historically faced by children living with HIV. Developing treatments adapted to children’s needs has never been a priority for the profit-driven model of pharmaceutical research and development, mostly because mother-to-child transmission of HIV is well controlled in high-income countries, and not many children go on to develop HIV.

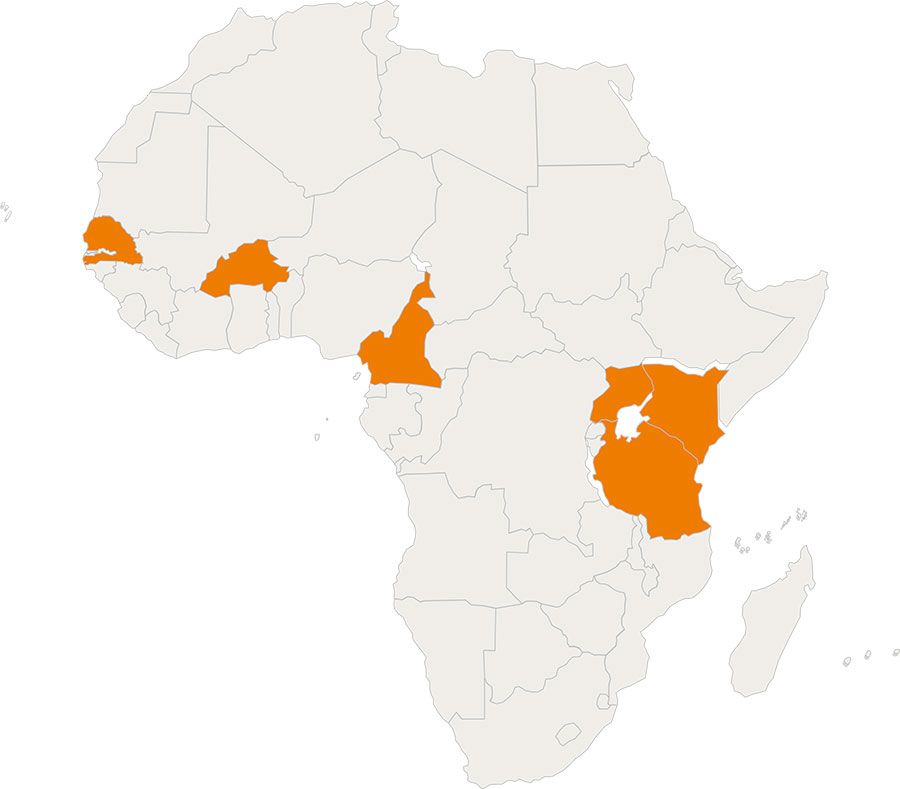

In 2020, DNDi, with financial support from the French Development Agency (AFD), launched the REACH programme (Revolutionizing Access to Quadrimune for Young Children Living with HIV) in six African countries: Burkina Faso, Senegal, Cameroon, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. The objective is to facilitate access to paediatric treatments and improve prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

Countries involved in the REACH programme

Countries involved in the REACH programme

In Burkina Faso, Senegal, and Cameroon, DNDi partners with Réseau EVA, a regional paediatrician network based in Dakar that aims to improve coverage and care for children living with HIV in Francophone Africa.

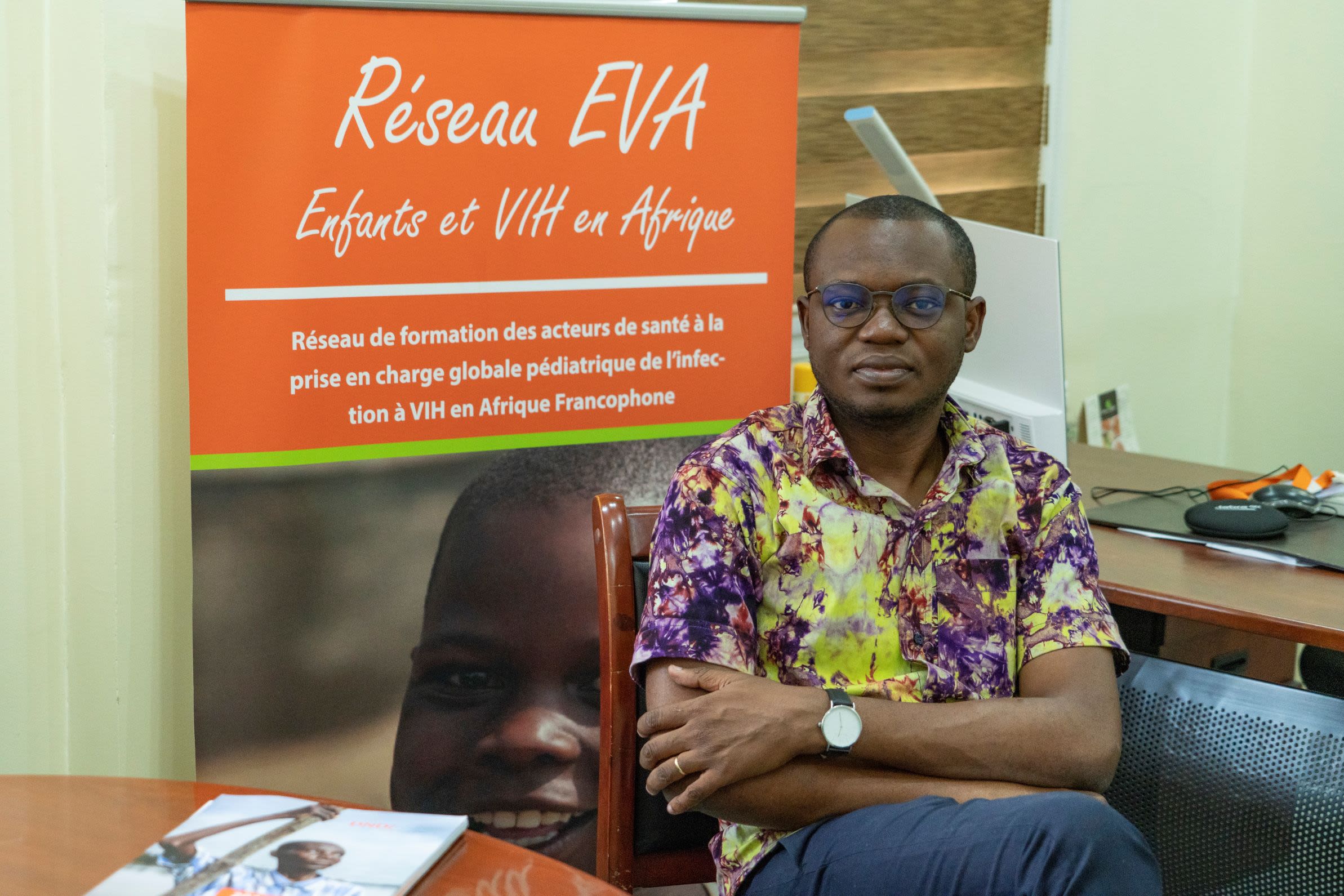

Réseau EVA's office in Dakar

HIV reference laboratory in Abass Ndao hospital, Dakar, where viral loads of children with HIV are measured.

HIV reference laboratory in Abass Ndao hospital, Dakar, where viral loads of children with HIV are measured.

Dr Gérès V. Ahognon, Executive Director of Réseau EVA in Dakar, Senegal

Dr Gérès V. Ahognon, Executive Director of Réseau EVA in Dakar, Senegal

DNDi and EVA have trained 70 trainers and 180 healthcare workers in the use of paediatric formulations recently brought to market. These healthcare workers will train their peers in the rest of the country.

The programme, which ended in March 2023, also includes support for transporting samples to the reference laboratory in Dakar that regularly measures patients' viral load – which is critical to monitoring and adapting treatment regimens.

DNDi also receives support from the Principality of Monaco to strengthen the capacity of healthcare workers to respond to paediatric HIV at 21 sites in the Dakar region. Case discussions, webinars, and trainings are provided to help healthcare workers better help children and adolescents living with HIV.

‘Everyone tends to forget HIV, especially in children. Yet the stakes are high,’ says Dr Gérès Ahognon, Physician and Executive Director of the EVA network. But what is the reason for this lower interest in children living with the disease? ‘It may be due to a comparatively smaller number of children with HIV here than in other countries.’

‘In Senegal, an estimated 4,000 children are living with HIV. But only 40% of them are diagnosed and receive treatment. Even though the numbers are not as high as elsewhere, we have every interest in taking better care of these children. Mothers who know they are HIV-positive are often reluctant to be tested because of the stigma attached to it. Despite the efforts of the government and partners, many children are missed by the mother-to-child transmission prevention programmes.’

The REACH programme also includes support for discussion groups. These groups give mothers a safe space to exchange advice and testimonies in complete confidence, find some relief, express what they cannot share elsewhere, and become better informed about the disease.

At the Albert Royer Hospital, these discussion groups are held twice a week. At each meeting, a theme is launched.

‘What time of day do you give your child the medicine?’ asks Astou Diop Dieye, a veteran counsellor who is a pillar of the mothers' ward. The mothers answer. Questions and advice flow freely. Astou gives a brief recap, then throws another topic: ‘Does the medicine kill or just put the virus to sleep?’ There are new answers. Tears well up, and crying mothers are comforted. At other times, there is a lot of laughter too.

‘This group makes everything easier. The moms care about each other, we can call each other afterwards,’ testifies one of them, a national from a neighbouring country, whose 12-year-old son was diagnosed 10 years ago.

‘His father passed away, and when I learned about my status I cried like never before. I was alone, without family, in a foreign country. I almost went crazy. Here I found support and the strength to continue.’

A grandmother in a red bubu who cares for her orphaned grandson explains that no one else in the family knows the child's status.

‘The only person I informed was his big brother, who is 20,’ she says. ‘I chose him because he is very responsible. I gave him some of the medication, explaining that the child should not take it in front of the family. I told him, “If I die, please take care of your little brother. No one knows about this but you.”’

The need for paediatric formulations is also discussed during the meeting. ‘Adult formulations are not suitable’; ‘the tablets are too big’; ‘the tablets are so bitter, the bad taste stays in the mouth until the next day’; ‘we would like discreet medicines, if possible...’

Paediatrician Ndèye Fatou Diallo explains why the absence, until recently, of formulations tailored to children's needs poses immense problems for treatment adherence. ‘The lopinavir-ritonavir syrup formulation needs to be kept in the fridge, and it tastes so bitter that children spit it out. The tablets for adults are enormous, forcing moms to cut them into small pieces that are complicated to dose. Paediatric formulations facilitate adherence. They also make it possible to give treatment earlier. Paediatric formulations are a joy!’

For decades, children living with HIV have been a particularly neglected population: there were no paediatric formulations as profit-driven pharmaceutical research and development had little financial incentive to develop treatments. The absence of paediatric formulations partly explains why children account for 15% of all HIV-related deaths, while only 4% of all people living with HIV are children.

But the tide has turned in recent years with the introduction of new, improved formulations for children – constituting what seems like a long-awaited treatment revolution for children living with HIV. First and foremost, countries have been introducing paediatric dolutegravir, which is now the WHO's recommended first-line HIV treatment. DNDi and the Indian pharmaceutical company Cipla have also introduced the 4-in-1 (known as Quadrimune), a combination of four antiretrovirals. The 4-in-1 has a strawberry flavour and comes in capsule form containing a powder that is easy to mix with food. It has already obtained market authorizations in South Africa, Mali, Uganda, and Kenya.

This progress is welcomed by Dr Gérès Ahognon:

‘When you have tablets that need to be broken into small pieces and that children spit out, it is difficult for mothers, especially when there is a heavy psychological burden, and they have to hide! The '4-in-1' is soluble, you can put it in a porridge and give it to the child. With these new paediatric formulations, we hope the situation will improve.’

Pictures by Mamadou Diop-DNDi and Xavier Vahed-DNDi

The Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) is an international non-profit research and development organization that discovers, develops, and delivers safe, effective, and affordable treatments for neglected patients.